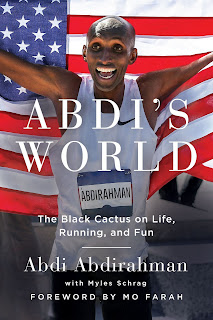

Abdi’s World

1.How did you get into running to begin with?

I never ran until I was a freshman in college, and I had no

interest in trying it at all even then. But I would eat lunch with my friends

at Pima Community College who were on sports teams and when they left for

practice I was bored. A friend told me I should talk to the track coach about

running. I showed up the first day in jean shorts and work boots and beat

everybody but one guy in a five-mile run. At Pima and then at University of

Arizona, I was successful at running and I made great friends being part of

those teams. I was still learning English and getting comfortable in America,

so running was a place of belonging then. It still is.

Sydney in 2000 happened so fast and it feels so long ago

that it’s hard to even answer the question. Every Olympics is unique, but I

remember the people of Sydney being friendly and the city being so clean. I was

only 23 years old. I had just become a professional runner and was still

learning who everybody was and about the history of the sport. I didn’t even

think making a career of running was a

possibility for me until a few months before the Sydney Olympics.

When I ran the 10,000 meters at the Olympic Trials in

Sacramento to qualify for Sydney, my feet were hurting midway through the race

because I was wearing new spikes. I remember wanting to make the team so badly

and not wanting to wait another four years to try it again. I fought through

the pain and that was a big accomplishment. So by the time I got to the

Olympics, I remember feeling like I had so many possibilities ahead of me.

Sydney represented that to me, and I knew that I wanted to come back to the

Olympics every chance I got.

I’m very proud of the race I ran at the 2020 Olympic Marathon

Trials to qualify for my fifth team. I prepared well, I knew I was in a good

position to make it, and I made good decisions throughout. As I wrote in my

book, “My wisdom and fitness, my past and present, were all aligned.” I did

something no American distance runner has ever done, and that felt really

satisfying.

I can’t say I appreciate the experience more now than I did back

in 2000 because I always knew how difficult it was to make the team. It takes

extremely hard work, smart racing, and some luck to qualify for the Olympics. I

always say age is just a number, but maybe now I don’t take for granted having

lots more opportunities left. I will have to retire at some point!

4.Tell us more about your running philosophy?

a.

Rock steady. Don’t get too down after a bad

experience and don’t get cocky because you did well. Some days are better than

others, and you can’t change that.

b.

Practice balance. When I train, I train hard!

But I also make time for friends and relaxing outside of running. I think

balance is the main reason I’ve had such a long career.

c.

Stick with what works. I’ve worked with Coach

Dave Murray since 1997. I’ve been sponsored by Nike since 2000. I run a lot of

the same trails in Tucson and Flagstaff that I’ve been running forever. I don’t

change my diet dramatically or track my workouts obsessively. When you change

things all the time, you create stress for yourself. And you’re likely not

addressing the core issues anyway.

d.

Play the long game. Don’t make decisions for

short-term gains. My best example of this was when a nagging injury kept me out

of the 2016 Olympic Marathon Trials. I desperately wanted to make my fifth

Olympic team that year and I was in fantastic shape. I could have taken a

painkiller or fought through it to try to race, but I would have risked a

bigger injury. I want to be able to run long after I stop competing as a pro so

I backed out. I healed and that fall I placed third at the New York City

Marathon. I was also more motivated to come back in 2020 to make my fifth team,

and that has led to experiencing the pandemic in a more thoughtful way, since I

qualified just a couple weeks before the world shut down.

e.

Give yourself 10 minutes. Even I sometimes don’t

want to get out the door. Everybody has those days, whether it’s going to work

or running or anything. I know if I give myself 10 minutes though, my body will

start to do what it’s meant to do. I’ll get what I call the “magic sweat” and

then I’ll be able to tackle my goal for the day.

5. How do you get ready for the Olympics? What is your

training like?

The past two Olympic cycles, I’ve gone to Ethiopia for

altitude-training camp before the Trials. I train with several friends, like Mo

Farah and Bashir Abdi, who are the best in the world, and we push each other in

workouts and hang out together. I get the benefits of altitude, fitness, and friendship

all in one! I have always done a lot of training on my own, but training

partners increase the intensity when I need it.

I don’t do as many super hard workouts anymore, maybe one or

two a week instead of three. I push as hard as ever on tempo runs and hill

workouts, then give my body plenty of rest.

6. What are you most looking forward to in Tokyo?

This is going to be a very unusual Olympics; there’s no

question about that. The marathon is hundreds of miles away from Tokyo, in

Sapporo, so I won’t be at the Athletes Village. I won’t attend the Opening

Ceremonies, which is like a big party and I always attend (even though my coach

says it saps your energy and tells me not to)! We won’t have spectators from

all over the world in attendance since international visitors are not being

allowed due to covid.

I will soak in this experience as I have all the others. I’m

honored to represent the United States and happy that I get to travel to a new

place and experience another culture. To be able to be part of the Olympics in

this unusual moment in world history feels even more special in a way.

7. You had to leave Somalia and live in a refugee camp before ending up in the US. How has that experience shaped you?

It has made me grateful for what I have and also to not

expect anything to be given to me. I don’t make excuses and I don’t assume I

know what somebody else is going through. Life is not always fair, so you have

to decide what you’re going to do with that reality. For me, I want to be

around positive people and make people happy when I’m around them.

I have not talked much about being a kid in Somalia and in a

Kenyan refugee camp until my book. I always wanted to focus on being the best

runner I could be and not get bogged down in sadness. The choices my parents

made when the country was destroying itself, how close we came to being on a

boat of refugees that wrecked, my sister being born prematurely right after we

arrived in Kenya…these are all things that feel heavy. But they are also an

opportunity for incredible gratitude.

Working on the book at this point in my life, especially

during covid, has been a liberating experience. I see how those difficult times

for my family have helped shape me in ways I never realized when I was younger.

The book has given me a chance to talk about high points and low points with

family and friends and decide what I think about those experiences as a

44-year-old.

8. How do you maintain a positive attitude?

Maintaining a positive attitude is a choice. It’s that

simple. We all have stuff going on in our lives every day that can sap our

energy or lift us up. I’m no different. I know that negative people and

arguments and conflict and excuses are not going to serve me or my goals.

People say I’m laid back and goofy, and I have to admit that is true. In part,

that’s probably a way to distract myself from negativity. But it’s also a

reminder that if you’re not having fun in life, you probably aren’t going to be

doing what you like or be motivated to stick to your goals.

There’s a reason the subtitle of my book is “The Black

Cactus on Life, Running, and Fun.” I’ve got lots to say about my life in and

out of running, but if I’m not making fun a part of it, I’m missing out. That’s

what I want readers to get out of the book.

9. Anything else you would like for readers to know?

I get asked a lot what advice I have for young runners, and

I always say that they should listen to their coaches, not compare themselves

to other runners, have fun, and don’t overtrain. The same thing is true with

anything in life: Listen to mentors you trust, don’t decide what you like based

on what other people think you should like, and don’t try to solve all your

problems right now. You’ve got a lifetime to figure stuff out. Above all, have

fun in whatever you do in life.

I don’t know what the Olympics are going to be like, I don’t

know what next year or 25 years from now is going to look like, and neither do

you. The fun is in the experience—but YOU have to decide to make it fun.

This book may have been received free of charge from a publisher or a publicist. That will NEVER have a bearing on my recommendations. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases if you click on a purchasing link below.#CommissionsEarned

No comments:

Post a Comment